on

Filter or Be Filtered

Eli Pariser’s talk, Beware online “filter bubbles” recently hit the front page of the TED Talks website. I found it interesting because it discusses some of what I’ve seen happening online, and some of my fears for how we search and consume content. Watch the video if you haven’t to see just how much is already being filtered on the web for you.

Right after I saw the video, of course, Facebook announced that they’ll be rolling out a new version of the the news feed. They are quoted as making it more like a “personal newspaper” — a filter, essentially, for the things Facebook thinks you want to see. As the video above pointed out, they’ve already been filtering out the things they think you don’t want for awhile.

No doubt there will be some backlash as people adjust to changes on Facebook, but very few will abandon it. And if you are the kind of person that would abandon Facebook over filtering, or privacy, or concerns about owning your own data, you don’t have a lot of choices of where to go.

Sure, you can specifically seek out services that aren’t going to give you a filtered world view — DuckDuckGo comes to mind. But that’s not always possible. The problem is bigger than just the search engine you use and whether or not you’re logged into Facebook. Just about every site is run by someone else, and they are analyzing you constantly. They are in a brutal battle to keep you as their consumer and keep you from going to other sites. But are the things that they think you want to see what you really want or need to see?

As a developer, I’m capable of taking matters into my own hands, to some degree. Most of the sites that I use on a daily basis have an API and allow me to export or scrape my personal data. But the cost of switching off of the nice service, the well-designed UI/UX of an official mobile app, and so on has kept me from taking the plunge to export my data and go set up shop on my own version of various web services.

Recently I revamped a very old, empty repo that I had on Github. The point of this repo was code a way to export all of my data from Last.fm. But for whatever reason the repo has been empty for something like 4 years now. So the other week, I sat down, checked the Last.fm API docs, and wrote a very simple Ruby script to dump out all the JSON it could about my top tracks, artists, and albums over the past 7 years. That script is available as my birdsong repo on Github.

So far, I don’t have a real use for the data. I could try to use some visualization tools on it to make cool graphs or maps. Or I could try and get analytics out of it: genres listened to, how they’ve changed over the years. But for now, I am content to just have the JSON data.

All in all, it’s around 30 megabytes of JSON data, which is really just plain text with no compression, so it is really quite a lot of data. There’s more I can do, though. I plan to do to start taking control, to both aggregate my own data and filter it.

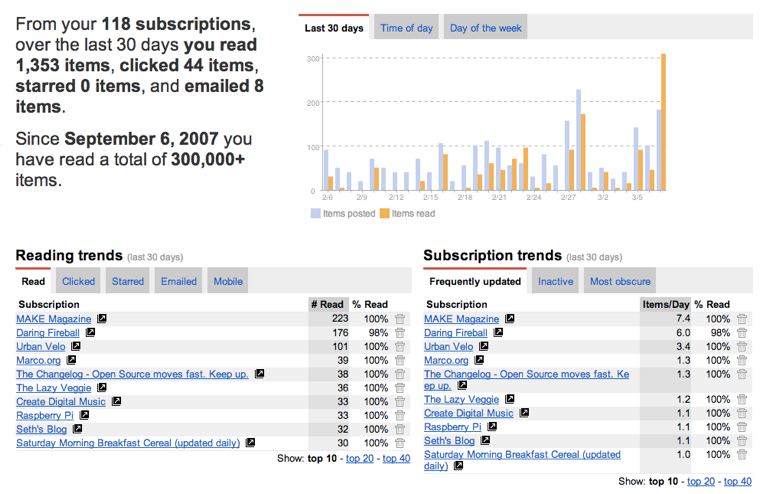

For a long time it has bothered me that Google Reader stopped receiving new features, and the features that existed only went so far. To be fair, Google Reader has been a rock solid web service for many, many years for me. It allows me to read my feeds quickly, reliably, and has parsed feeds well — all problems I’ve had with other feed readers. It’s always had some neat features like showing me analytics of what I read.

But as far as discovering new content and helping me to eliminate content I don’t read or don’t want to read, Google Reader is not so great. Reader is terrible at suggesting new feeds to read to me; it constantly suggests Dilbert and Lifehacker, and has for the past 5 years or so. I have no interest in either of those. It has never analyzed my reading patterns to such a degree that it suggested something new that blew me away. I am looking for those kinds of interesting suggestions: not just for feeds that match what I already read, but things that are outside of my normal bubble but would be interesting to me.

Luckily, Google Reader has an API, and rather than just exporting my data and building a new service, I can start to build off of it. I get to keep a lot of the features I enjoy while extending it with my own code.

In Pariser’s talk, he talks about encoding algorithms of filtering and recommendation with a sense of civic duty. To some degree, this means having some journalistic integrity. Such an algorithm needs to present both sides of the story. One issue of many feed readers and other content online is that, well, it only shows one view. The view of the article you’re on.

But imagine a feed reader that was more like the front page of Google News. It would not only show you the blog post you’re reading, but all recent blog posts from other authors about similar topics. Maybe, if they’re responding to a news event or writing about a known fact, the reader could do the work to track down the original source. To take it even further, without even really needing to be aware of motive, politics, and other factors, a dumb feed reader with good suggestions could probably present both sides of the story. Both sides of an argument. Both liberal and conservative takes on the same bill.

Dreaming up features like this can be a deep rabbit hole. Start considering the consequences of pulling up all past articles you’ve read about similar keywords or tags. Or performing searches for academic papers on the topic. Pulling in data from Wikipedia. Looking up books you’ve read or are planning to read on Goodreads that are related to the blog post you’re reading. Or any other number of ways to slice and dice content. And it doesn’t have to stop with Google Reader.

Opportunities to make better tools and more intelligently consume information are all around us. At the same time, consumer-consuming corporations on the web try to trap us into filter bubbles. They try to provide us with what they think we want, but can they ever really know? In the end, it’s control-your-own-filters or be filtered1.

1 The name of this article was lifted from Daniel Rushkoff’s Program or be Programmed, a book which I didn’t really enjoy. It was not what I thought it would be about: why we should learn to program so that we can control the complex technical systems around us rather than be controlled by them, or how programming’s problem solving skills can be applied elsewhere. Instead, I found the book to be some technology-fear-mongering and a bunch of diatribes about how things online or in computers are “less real.” Suffice to say, I did not enjoy it. ↩